Originally published by our sister publication Pharmacy Practice News

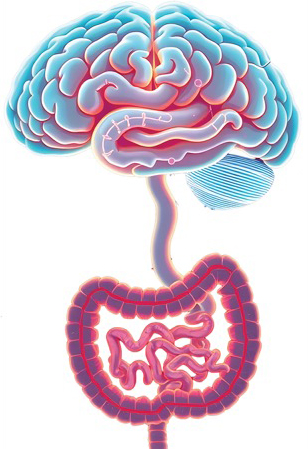

The gut–brain–microbiome (GBM) axis is a two-way street, with gastrointestinal symptoms affected by stress and acting as a stressor, an expert noted during the American Association of Psychiatric Pharmacists (AAPP) 2025 annual meeting, in Salt Lake City.

“Chronic stress affects all levels of GI functioning, down to the microbiome,” said Brian Arizmendi, PhD, a GI health psychologist at Mayo Clinic, in Phoenix, Ariz. Stress-induced disruptions of the GBM axis have been linked to various GI disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), as well as a wide variety of mental health conditions, including anxiety and depression.

The mechanism underlying the gut–brain axis involves bidirectional communication between the central nervous system (CNS) and enteric nervous system (ENS), allowing the CNS to influence gut function and vice versa, Dr. Arizmendi noted. Indeed, the ENS is sometimes referred to as the human body’s second brain because of the vast, complex network of neurons it contains that permit it to autonomously regulate GI processes, independent of the CNS, he noted.

The stress that often drives these processes “bring the stomach and small intestine function nearly to a halt, or at least slows it down significantly,” Dr. Arizmendi said. Over time, he noted, stress can reduce the richness and diversity of the gut microbiome. “We also know that early life adversity and traumatic events can be predisposing factors for these disorders. A history of depression, anxiety, chronic stress, medical complications, medical trauma—all are going to increase that chronic stress response.”

Gut Instinct

There are 33 recognized disorders of gut–brain interaction (DGBIs)—a term that has replaced “functional GI disorders” as more descriptive and less stigmatizing—each characterized by a unique combination of symptoms related to GI function and psychological factors. The global prevalence of DGBIs is estimated at approximately 40%, according to the landmark Rome Foundation Global Epidemiology study (Neurogastroenterol Motil 2022;34[8]:e14323). A related study from the same database (Neurogastroenterol Motil 2024;36[12]:e14940) found that DGBIs involve clusters of symptoms with pathophysiology marked by some combination of altered:

- motility;

- visceral sensitivity;

- the gut epithelial barrier;

- mucosal immune function;

- the microbiota; and

- gut–CNS neural processing.

“No anatomical or structural abnormality is identifiable in these conditions, and no curative treatments are available for any of these conditions, at least not yet,” Dr. Arizmendi said. “So the approach is on symptom mitigation. For patients with mild symptoms, lifestyle factor changes can be enough, such as adding fiber supplements, increasing water intake and exercise.” But for patients with moderate to severe disease, “that’s where we have to consider pharmacologic and behavior therapy interventions.”

Anxiety is the most common presentation co-occurring in people with GI symptoms, and GI-specific anxiety about stressors such as the availability of a bathroom can be superimposed on a history of generalized anxiety, Dr. Arizmendi said. “You get something of a vicious cycle starting to happen, and that’s why anxiety is so prevalent in this population.”

Unsurprisingly, he added, as people start to lead more restricted lives due to their illness, “they start to feel like they’re being controlled by their symptoms, which can lead to depressive disorder pretty quickly.” There also is some evidence for a correlation between panic disorder and DGBIs, Dr. Arizmendi noted (Neurogastroenterol Motil 2023;35[2]:e14493).

As for pharmacologic options, “opiates might be prescribed for chronic abdominal pain but can themselves be constipating, as well as being linked to substance use disorder,” he said. Another challenge is posed by the use of marijuana. “We are seeing more and more cannabis-induced hyperemesis in our clinic, as cannabis is legal in many states,” he said. “Sometimes people will think they can use cannabis to treat their nausea, when all they may be doing is perpetuating some of their symptoms.”

Team-Based Care

Dr. Arizmendi recommended a multidisciplinary approach to treating DGBIs, with the GI condition typically managed as the primary presentation, alongside complementary treatment of co-occurring psychiatric illnesses that may be contributing to or exacerbating the GI symptoms. “What we are really targeting here is the relationship between the two,” he said.

In the case of IBS, 55% of U.S. GI specialists say they use central neuromodulators such as antidepressants to managing the condition (Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2021;54[3]:281-291). These medications exert their effect through neurotransmitter modulation, explained Camille ThÉlin, MD, the co-director and co-founder of the Neurogastromotility Clinic and director of the Women’s Digestive Diseases Health Program at the University of South Florida, in Tampa.

Although evidence-based research on using central neuromodulators for DGBIs is limited, “clinical experience, expert consensus and open-label studies suggest they are highly effective, and we do use them as first-line therapy,” Dr. ThÉlin said in a separate interview with Pharmacy Practice News. “The problem is that it is not one size fits all, and it can take up to three months to see a full effect, because we are usually starting at low doses and titrating up to see full efficacy.”

Managing DGBIs with central neuromodulators is a very individualized process, Dr. ThÉlin added. “Medications such as tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs], serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs] and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs] are all neuromodulators, but they vary in how many receptors they affect,” she explained. “TCAs, being the oldest, are broad-spectrum and act on multiple receptors. So in more complex cases that haven’t responded to standard approaches, a TCA may be helpful.” She further noted that TCAs can target nausea, vomiting, pain and even aid sleep due to its sedating effects. “On the other hand, if a patient has a strong history of anxiety or depression, I might opt for a more modern, targeted agent like an SSRI or SNRI.”

Pharmacologic treatments for DGBIs often are paired with behavioral interventions, with cognitive behavioral therapy having the most evidence behind it (Clin Med [Lond] 2021;21[1]:44-52). Such therapy “addresses maladaptive thought patterns and catastrophic thinking, and works through exposure and behavioral activation to push back against any sort of avoidance coping mechanisms that further limit people’s lives and reduce their quality of life,” Dr. Arizmendi said. “It is most well researched in IBS, but there are several other conditions where it’s known to be helpful.” Other options, he added, include hypnosis therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction and interpersonal therapy.

Dr. ThÉlin advised partnering closely with the patient to explain why a specific course of treatment is being recommended. “A lot of them have been searching for answers for a long time, and they are very frustrated, which has often led to doctor shopping and fractured management,” she said. “That in turn results in more stress and further amplification of symptoms, which becomes a vicious cycle. We need to earn their trust, especially when thinking of using drugs that sometimes can take up to three months to see a full effect. If they understand what the goal is, how long it might take to reach that goal and why we are taking this approach, it goes a long way.”

The sources reported no relevant financial disclosures.